Federal judges this past week ordered a redrawing of the lines between Congressional Districts in North Carolina, while the Supreme Court agreed to hear an appeal of a similar ruling in Texas. And then there's Pennsylvania -- which features a Congressional map that, some critics say, looks like a cartoon. Our Cover Story is reported by Mo Rocca:

"Goofy's over there, and he's kickin' Donald," said Bonnie Marcus.

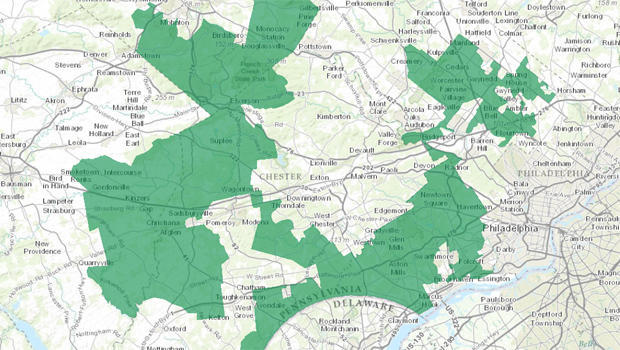

This is not a Rorschach test -- and these are not patients. They're suburban Philadelphia voters who live next door to Pennsylvania's 7th Congressional District, nicknamed "Goofy kicking Donald Duck" for its absurd shape:

A map of Pennsylvania's 7th Congressional District, encompassing parts of five counties in the Philadelphia suburbs.

CBS News

"His ears are flapping!" Marcus said.

"But wait a minute: Would Goofy ever kick Donald?" Rocca asked.

"Not and stay in the Disney World," Marcus replied.

This district is one of the most gerrymandered in America. It is, said Bill Wells, "a disgrace, a political disgrace. There's no reason for that kind of gerrymandering. Here it is, folks, right in front of you."

Welcome to Gerrymandering 101!

"Gerrymandering" is the manipulation of voting district lines, usually to give one party an advantage over the other.

The word comes from Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry, who in 1812 signed off on a salamander-shaped district, hence the term "gerrymander" (which sounds a lot better than "garry-mander").

There are 435 Members in the House of Representatives. Pennsylvania has a lot of people, so it gets 18 of those House seats.

Some of these shapes -- not just the 7th -- are pretty wacky.

Mo Rocca with a map of Pennsylvania's Congressional Districts.

CBS News

Now, you may ask: Why not just lay a nice rectangular grid over Pennsylvania? Problem solved, right?

Well, you can't do that, because people don't live evenly spread out, and each district has to have the same number of people. For that reason (and others we'll get to later) the shapes of districts are almost never going to be perfect squares.

But how these shapes got to be so wacky is the issue here. Pennsylvania Democrats say the Republican-controlled State House drew these lines -- or gerrymandered them -- to create as many safe Republican seats as possible.

Last election, Republicans won a little more than half (54%) of the statewide vote, but the lion's share of seats -- 13 out of 18, more than two-thirds.

"We're not getting the representation that we were intended to get," Wells told Rocca. "And the politicians just jiggle it around to meet their needs, not our needs."

They're angry because they say their Democratic-leaning communities were deliberately kept out of the 7th, and lumped into the heavily-Republican 16th District, ensuring that both went red.

"It causes people, I think, to wonder why should they even go out to vote," said Brenda Mercomes. "Is my vote gonna count?"

"It was done to us, personally," said Wayne Braffman. "And there is no rational justification for that other than lying, naked power."

Both parties are guilty of gerrymandering, and both parties have long decried it.

But increasingly the discussion around gerrymandering has been about the threat it poses to American democracy itself.

Few current representatives want to talk about it. Iowa's Rod Blum does: "We shouldn't have to rig the system in our favor, or the Democrats shouldn't have to rig the system in their favor."

Blum is a Tea Party Republican who represents Iowa's 1st, a Democratic-leaning district. Blum says he can't afford to ignore any of his constituents. "With gerrymandering, the politician knows that they can be extreme right or extreme left and get reelected," he said. "If the district was more like mine, split evenly, then you're looking at every bill -- 'What's a Republican think of this? What's a Democrat think of this? What's an Independent think of it?'"

His is not a typical district. Nationwide, gerrymandering is one reason that the number of competitive Congressional seats -- those where both parties have a good shot at winning -- has plunged over the last twenty years, from 164 to just 72.

District lines are redrawn every ten years, right after the census, usually by the state legislature, in a process known as redistricting.

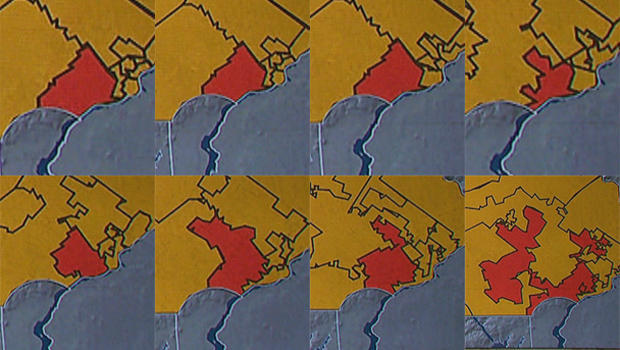

Get a load of how the Pennsylvania 7th has changed over the years:

The changing shape of Pennsylvania's 7th, from the 1940s to today.

CBS News

Few know this process better than Kim Brace. For more than 40 years, he's been hired (mostly by Democrats) to help draw Congressional Districts. He was the only mapmaker we identified that was willing to talk to "Sunday Morning" on camera.

Rocca said, "You've got a lot of power in your pen."

"That's true. [But] it's not your pen; it's now a mouse," Brace replied.

And armed with mountains of voter data, it's become more science than art.

"Theoretically, you could say to a Republican incumbent, 'Listen, the 5300 block of River Road is a lot more Democratic now. Let's cut that out when we draw the map'?" Rocca asked.

"Sure, sure. That's possible," Brace said.

But he says there are a lot of factors that have to be considered -- for instance, districts have to be contiguous, communities of interest should be kept together.

And how about this one? "Incumbent requests and incumbent protection -- there's something that the courts have recognized is a fact of redistricting life," Brace said.

"'Incumbent protection' -- like they're spotted owls?"

"Or something along that line, yes."

But this was precisely the rationale back in 2001 when, to protect the seat of Democratic Congressman Bobby Rush, Brace cut out a residential block, home to a young primary challenger named Barack Obama.

"You gerrymandered the future President of the United States out of a Congressional District?" Rocca asked.

"Right. So he then went for U.S. Senate, and used that elevation to then become president."

"Not even a president could do what you did!"

"Probably not, I guess!"

While the general perception may be that gerrymandering is bad for democracy, Brace says that's not always the case. "One person's gerrymander is another one's beautiful art creation."

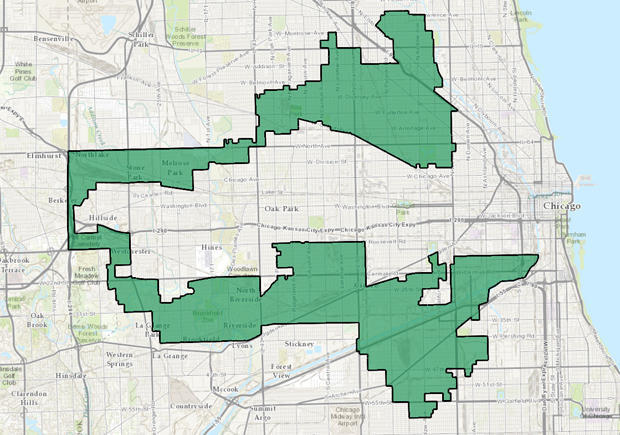

There may be no better example of this than Brace's most famous (or infamous) creation: Illinois' 4th, better known as "the Earmuffs."

It was drawn to comply with the Voting Rights Act, which mandates that racial minorities be able to elect "one of their own." And so, he connected two Latino neighborhoods on Chicago's West Side by a narrow highway corridor:

CBS News

And on each side of that narrow highway? The Illinois 7th, and the Illinois 5th.

Back in the '90s, it was racial gerrymandering like this that dominated the discussion. Then, in 2010 the GOP launched an ambitious campaign to win control of state governments and redraw the lines in their favor.

They succeeded in a big way.

"It was a sea change," Brace said. "We've now seen Congress being in control by the Republicans for this entire decade."

While Republican House candidates won about half (49%) of the nationwide vote in 2016, they captured 55% of the seats -- 241 to the Democrats' 194.

But -- and this is important -- even if lines were not being drawn to favor Republicans, Democrats would still be at something of a disadvantage, says Stanford political scientist Jonathan Rodden. That's because of where they live.

"Democrats have been clustered in cities in the industrialized states every since the New Deal, ever since FDR," Rodden said. "Cities have become more Democratic, and rural areas more Republican."

Rodden studies how increasingly Republicans are spread across rural areas and Democrats packed into urban areas. Consider the influence on a state like Missouri: "The Democrats are highly concentrated in St. Louis and Kansas City," Rodden said. "The gubernatorial elections are always very close. It's a place that Democrats can win statewide. But the best they can hope for in an eight-seat Congressional delegation is three seats, and the current outcome is two."

So, is the issue gerrymandering or geography? "It's geography and gerrymandering," said Rodden. "In order to understand the outcomes we see, we have to understand how those two things interact."

The issue of gerrymandering is before the Supreme Court right now, and a decision is expected this spring.

And Iowa's Rod Blum is willing to risk any advantage gerrymandering currently gives his party.

Rocca asked, "If putting curbs on partisan gerrymandering meant ceding control of the House to the Democrats, how would you feel about that?"

"I'm okay with it," Blum replied. "We need to recruit good candidates and we need to get out there and we need to do a good job of governing and we need to sell our message to the voters."

"Losing an election is no small thing!"

"And I think the opposite. I think if you lose an election, it's okay. That's the way our government was set up -- not to have these people be here 30, 40, 50 years."

As for our voters in Pennsylvania, the state court there is considering re-drawing the map. For them, a decision can't come soon enough.

"Everyone wants to be treated fairly," said voter Nancy Murphy. "Gerrymandering isn't fair. It's cheating. It's taking our votes and putting them where it won't make a difference."

For more info:

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Drawing the lines on gerrymandering"

Post a Comment