There were two exhibitions in New York this spring — to which you can now add a third — that shed new light on what was happening in abstract art in France after World War II. The first two exhibitions were François Morellet at Dia: Chelsea (October 28, 2017 – June 2, 2018) and Martin Barré at Matthew Marks (February 17 – April 7, 2018), which I reviewed.

These exhibitions, along with the periodic exhibitions, starting in 2010, of Simon Hantai’s paintings at Paul Kasmin, helped dispel the idea that the only interesting abstraction was happening in America, which certainly was never true. However, if you take Morellet, Barré, and Hantai, along with Yves Klein and Pierre Soulages, as a measure of what was going in abstract art in France, apart from the Support-Surface group, which has also gotten attention in New York in recent years, you get the mistaken idea that only men were making abstract art in France. We seem to have imported French chauvinism because it so perfectly complements our own.

This is one reason why the exhibition Vera Molnar: Drawings 1949- 1986 at Senior & Shopmaker (March 23 – May 12, 2018) should be on your list of things to see. The other more important reason is the work itself, which should always be case, but sometimes isn’t.

Covering nearly four decades, the works in this exhibition offer a fruitful glimpse into the trajectory of Molnar’s career, from post-Constructivist abstraction to drawings made according to a strict set of algorithmic rules to — in 1968 — her first use of a computer to make drawings, which she has continued to do for nearly 50 years. Born in Budapest in 1924, she is widely recognized in Europe as a pioneer in the use of a computer to make art. Other artists have used the computer, of course. Frederick Hammersley made a series of computer-generated geometric drawings in 1969, but Molnar was never interested in making any kind of imagery.

The journey she undertook is dazzling. Although there is nothing in the show to indicate Molnar’s beliefs, other than her devotion to establishing and following a strict set of rules, I was reminded of the opening statement in Sol LeWitt’s SentencesonConceptualArt (1969): “Conceptual artists are mystics rather than rationalists. They leap to conclusions that logic cannot reach.” The fact that she was a pioneer in the use of the computer and, by LeWitt’s definition, can be considered a conceptual artist gives us a glimpse into the unique terrain that Molnar occupies.

The exhibition contains work from four periods in her career. The first runs from 1949 until 1961, during which she aligned herself with the work of Russian Constructivism. During this period, she also took the work of Piet Mondrian and Paul Klee as starting points for her own investigations. For her, art was not about starting over or making a break. It was about pushing it forward into new areas of perception. Basic to this investigation was the relationship between the line and mathematics — what kind of rules could be used to make a drawing? Rules, of course, are central to three-point perspective and to Islamic geometric design. Josef Albers worked according to rules to learn how color interacted. LeWitt set up rules so that others could make his drawings.

Between 1959 and ’68, when she was first able to program a mainframe computer to make drawings, Molnar imagined herself to be a drawing machine, a “Machine Imaginaire.” She used the grid as a structure to determine the placement of a line or a color. By establishing a set of rules, she could predetermine how the line would shift from gridded square to gridded square. As dry as this might sound, the results are often tour-de-forces, in which the relationship between order and chaos is stretched beyond what the eye can comprehend, leaving this viewer at least in a state of visual awe.

In her hand-drawn “Distribution Aleatoire de 4 Elements (pour progr. ordinateur)” (1970), Molnar works an algorithm on a sheet of graph paper. On the left side of the sheet, she has created a gridded, maze-like square composed of short horizontal, vertical, and diagonal ink strokes, while on the right, she has meticulously plotted a matching graphite grid of alphanumeric cells, whose variations and repetitions provide a code for the number and direction of each subset of pen strokes.

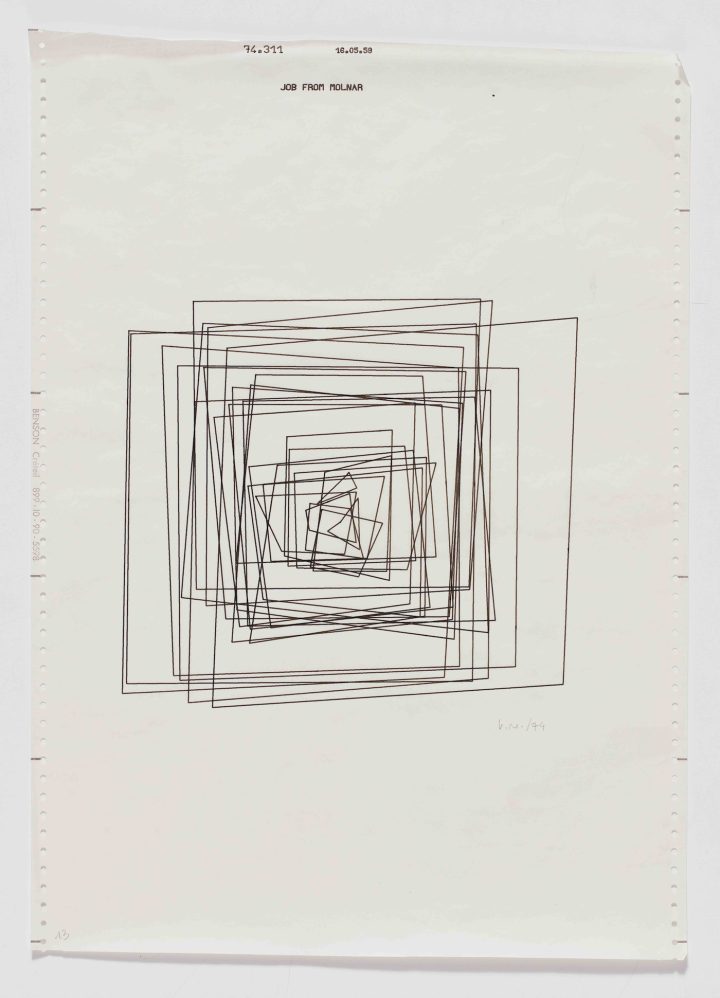

Once she was able to use a mainframe computer, the grid was dropped, leaving only a field of lines, sometimes in one color and other times in two. Drawings such as the two that are titled ”Inclinaisions” (both date 1971) generate a distinct visual buzz. In “Hypertransformation of 20 Concentric Squares” (1974), Molnar uses an algorithm to do something to each square, producing vibrating groups of them while issuing an invitation to see what is distinctive about each one.

With the drawings done on a mainframe computer, Molnar does not remove the perforated edges. They were “jobs” printed up according to her algorithm, an investigation into what was possible. She never tries to make a drawing representational: it is of no interest to her. In the mid-1980s, with the advent of the personal computer and advanced printing techniques, she obtained a computer and began to work at home, where she makes drawings in sets. In each one, she is intent on discovering what can be done with a line, and with geometric structures such as squares and rectangles. She keeps coming up with fresh possibilities.

In 2009, Thomas Micchelli reviewed Pierrette Bloch (1928-2017) at Haim Chanin Fine Arts for the Brooklyn Rail (June 2009). As he pointed out, it was the first time that Bloch had shown in the United States since 1951. This is one sentence from the review:

For decades, Bloch has streaked, dripped, and blotted ink on paper or Isorel, a highly frangible type of chipboard.

Bloch and Molnar are two very different artists who made drawings for well over half a century. Both happen to be women. The fact that they worked in France is another indication of how interesting the scene was there, and how that country’s preoccupations seem distinct from what was going in America. Maybe we should open our eyes a little more than we have.

Vera Molnar: Drawings 1949-1986continues at Senior & Shopmaker Gallery (210 Eleventh Avenue, 8th Floor, Chelsea, Manhattan) through May 12.

Read Again https://hyperallergic.com/437834/vera-molnar-drawings-1949-1986-senior-and-shopmaker-gallery-2018/Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "A Trailblazer of Computer Drawing Gets Her Due"

Post a Comment