New radiometric dating identifies the oldest known figurative drawing—not a stenciled outline of a hand or an abstract design, but an actual attempt to depict a real object in an image. As far as we know, a cave wall in Indonesian Borneo was the site for the first time a person drew something, rather than just making abstract marks. The drawing is at least 40,000 years old, based on uranium-series dating of a thin layer of rock deposited on top of the drawing since its creation.

It’s a large animal of some sort, outlined and colored in with reddish-orange pigment, but after 40,000 years, parts of the image are missing. Griffith University archaeologist Maxime Aubert and his colleagues say it appears to be a large hoofed mammal with a spear shaft sticking out of its flank.

Other figurative drawings, as old as 35,000 years, have turned up on the nearby island of Sulawesi, alongside hand stencils dating back to 40,000 years ago. And in Europe, people started representing animals in art around the same time, such as on figurines carved in mammoth ivory from Germany. That means the tradition of representing the world around us in art is ancient around the world, from an island in southeast Asia to western Eurasia.

The oldest artists

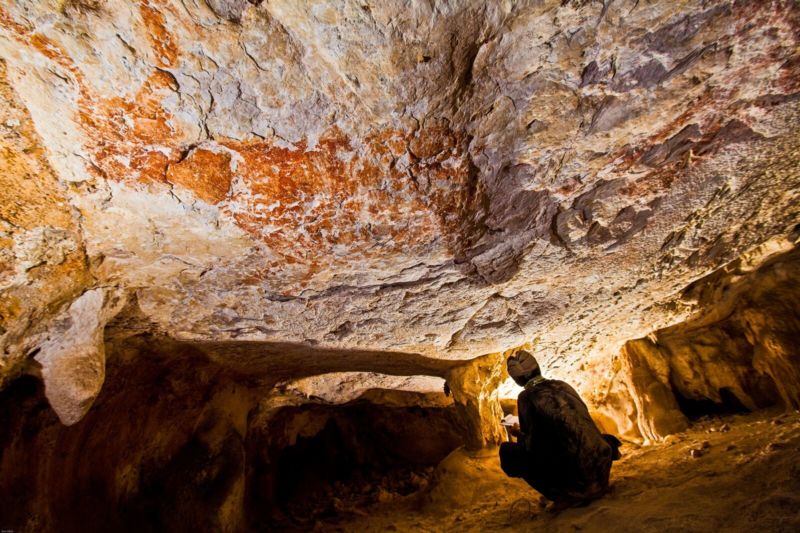

East Kalimantan, on the Indonesian side of Borneo, contains about 100 square kilometers of dense forests, mountains, and towering cliffs—challenging terrain to explore even today. But it’s worth the climb, because the forested cliffs are riddled with caves, and thousands of images adorn their walls: stenciled hands, abstract motifs, and human and animal figures in shades of deep purple and bright reddish-orange. Those images represent as much as 52,000 years of human art. The cultures that created it emerged here at the far southeastern tip of Eurasia—an important jumping-off point in our species’ spread into the islands of the Pacific.

Aubert and his colleagues sampled material from layers just above and below 13 cave paintings in six East Kalimantan caves. Dripping and flowing water constantly deposits new layers of rock in limestone caves, so most of the cave art has a thin layer of rock atop it. Over time, the traces of uranium-234 in that rock decays into thorium-230. By comparing the ratio of these isotopes, archaeologists can determine how long ago the newest rock layer was laid down—this provides a minimum age for the art beneath. The partial animal from Lubang Jeriji Saleh cave was the oldest, but two hand stencils from the same cave dated to at least 37,200 years ago, and another was drawn somewhere between 23,600 and 51,800 years ago, all in the same reddish-orange pigment as the speared animal.

Modern humans arrived in southeast Asia sometime between 60,000 and 70,000 years ago, but people on Borneo didn’t leave cave art behind to mark their presence for another 20,000 years or so. “What is surprising is why we don’t have cave art dating to the earliest arrival of humans in the region,” Aubert told Ars Technica.

He suggested that earlier paintings may still be waiting to be found and dated—archaeological work on the island has been limited so far. But the sudden emergence of art could be linked to an increase in population between 50,000 and 40,000 years ago. The Borenan banteng, a species of wild cattle, was an especially popular subject, but other animals make appearances, including a few species that may now be extinct on the island.

-

Limestone karst of East Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo.Pindi Setiawan

-

Aubert et al. 2018

-

Human figures from East Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo. This style is dated to at least 13,600 years ago but could possibly date to the height of the last Glacial Maximum 20,000 years ago.Pindi Setiawan

-

Composition of mulberry-coloured hand stencils from East Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo. This particular style of hand stencil dates to the height of the Last Glacial Maximum about 20,000 years ago.Kinez Riza

Ice Age cultural upheaval

Dating the cave paintings hinted at a couple of major cultural upheavals in Borneo’s distant past. Around 21,000 years ago, during the height of the Last Glacial Maximum, ice sheets covered the northern parts of North America, Europe, and Asia, while Borneo’s climate would have been more temperate than it is At this time. the reddish-orange painted hands and animals gave way to images painted on the cave walls in dark purple pigment: small human figures now called Datu Saman and hand stencils filled in with complex patterns of lines, dots, and other abstract shapes.

Aubert and his colleagues say those designs may represent tattoos or other ornaments that marked a person’s social status, family membership, or other identity. And some of the hands are linked by complex networks of lines, like a modern family tree. Even some of the older, reddish-orange hands, which would have been ancient at the time of the Last Glacial Maximum, have been touched up with the purple designs, as if the artists wanted to connect those earlier islanders to their own culture.

The timing of this change is probably no coincidence. “At that time, the global ice age climate was at its most extreme, and perhaps life in these harsh conditions stimulated new forms of cultural innovation,” Aubert told Ars Technica. “Or perhaps East Kalimantan was a refugia for humans, leading to an increase in population density.”

As the island’s population grew, scattered groups of people would have come into contact with their neighbors more often, and they may have grown increasingly concerned with things like territorial boundaries, group and family membership, or social status. On the other hand, a new wave of settlers could simply have replaced the island’s earlier inhabitants, bringing a new culture and art style with them. That’s a question about Borneo’s distant past that more archaeological work may eventually answer (and it’s one of many).

The human figures start to appear on the cave walls around 13,600 years ago, at a time when the ice sheets still dominated the world’s northern latitudes but had begun to slowly recede. Most of the time, they’re drawn wearing elaborate headdresses and carrying spears, spear throwers, and other objects. Sometimes they show up in groups, and sometimes they’re hunting or dancing.

Anonymous artists, for now

Borneo’s cave art offers interesting hints about how and when people moved into the region. The first two phases of art haven’t turned up anywhere else on the island, but around 4,000 years ago, people started drawing human figures, boats, and geometric designs in black pigment on the walls of caves like Lubang Jeriji Saleh. That style of art appears in caves across the island, and Aubert and his colleagues say that based on the timing and distribution of that ancient artwork, it may be the work of groups of farmers who moved into the region from mainland Asia around 4,000 years ago.

The oldest art in Borneo remains mostly anonymous. Archaeologists don’t have enough evidence yet to know whether the people who drew the first mortally wounded bantengs on cave walls were more closely related to the ancestors of modern Australo-Melanesian groups, who would have been the first wave of modern humans to pass through the region. and eventually settle in places like Sahul and Australia. Alternately, the artists may have been the ancestors of modern east Asians, who might have settled Borneo in a second wave around the time the first rock art appears. It’s going to take more archaeological evidence, in the form of fossils, artifacts, and more dated cave art, to identify the ancient artists.

“We want to date more rock art in Borneo and Sulawesi, but we are also going to start archaeological excavation in Kalimantan,” Aubert told Ars Technica. “We want to know who the earliest artists were.” The team plans to begin that fieldwork within the next year.

We can make better guesses about where those artists went than about where they came from. The nearby island of Sulawesi contains its own wealth of cave art, most of which is just slightly younger than the oldest artwork on Borneo.

“We think that possibly the rock art from Sulawesi came from Boreno,” Aubert told Ars Technica, adding that cave art may have spread from there all the way to Papua New Guinea and Australia. And that tradition of art, which seems to have spread throughout the islands of southeast Asia and Oceania from its origin in Borneo, sprung up independently at around the same time as the earliest art on the other side of the world, in the well-known caves of Spain and France.

Nature, 2018. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-018-0679-9 (About DOIs).

Read Again https://arstechnica.com/science/2018/11/the-worlds-oldest-figurative-drawing-depicts-a-wounded-animal/Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "The world's oldest figurative drawing depicts a wounded animal"

Post a Comment