This article is edited from a story shared exclusively with members of The Masthead, the membership program from The Atlantic (find out more).

“It's a hard time to tell the truth in Egypt,” says Magdy El Shafee, cartoonist and co-founder of the annual Cairo Comix Festival. “And it's getting harder.”

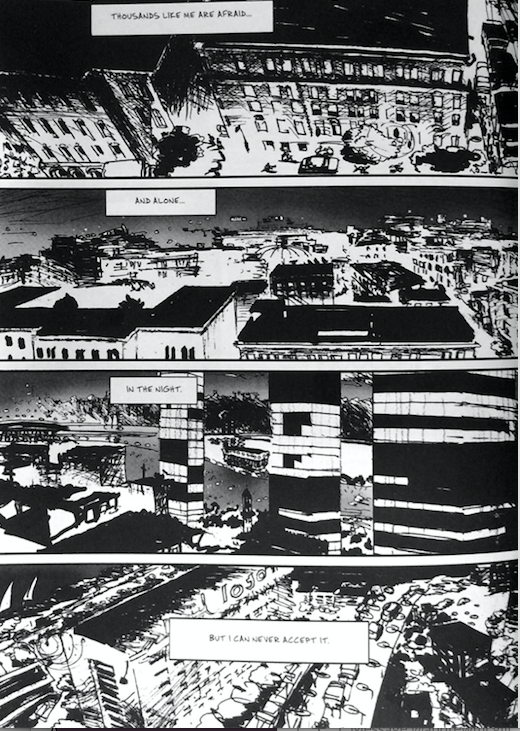

For four days in September, in a courtyard on the old campus of American University in Cairo, El Shafee’s festival brings together a thriving creative community of artists using comics as a bastion of personal and political expression. In the cartoons and illustrations on display at the festival there are common threads and urgencies. Again and again, you find small figures adrift in dense environments, overwhelmed by huge foes, straining in the cramped confines of claustrophobic panels. Isolated characters struggle against their own backgrounds, on the verge of being swallowed into the ominous shadows of ink-drenched cities. The images mirror the stories of their creators, who have fought to maintain their authentic graphic voices while the repressive state that has emerged since the Arab Spring surrounds them on all sides.

After Egyptians overthrew longtime dictator Hosni Mubarak in 2011, a moment of political openness allowed political art to flourish. “During the revolution art was exploding everywhere,” says El Shafee. “In graffiti on every wall of the city, in the new independent comics and magazines we began publishing. It was all the same artists—the Cairo underground. Everywhere, we were drawing the truth.”

Now, with the military in charge under Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, who seized power in a 2013 coup, political repression is back. Sisi's military regime is the third-worst jailer of journalists on the planet. A new law against “abusive graffiti” has ended the culture of dissident street art.

Despite a small readership—or perhaps thanks in part to their relative invisibility—comics in Egypt are blossoming in the shadows. “There is no distribution in Egypt. There are no graphic novel publishers. There is no real way to make a living publishing comics here,” says Sara El Masry, co-owner of an organization called MAZG that runs cartooning workshops throughout the country. But as other means of expression have been shut down, the cartoonist festival has grown, according to its organizer. With few eyes on them, these graphic storytellers are depicting the truth as they see it.

The price of that kind of daring can be high. Ask El Shafee,called by Newsweek “the godfather of Egyptian graphic novelists.” He was arrested by the Mubarak government for publishing Metro, a 2008 graphic novel with political undercurrents. “It is very hard to find a space here that is open to material of all different kinds. Work dealing with sexuality, politics, religion. There is always danger there,” El Shafee says.

In 2015, El Shafee joined forces with the cartoonist and designer Mohammed Shennawy and organizer Lina Monzer to create the festival. The founders make their values clear. In response to an inquiry from Egyptian art student Mina George Maurice about the festival’s policy on objectionable content, El Shafee wrote on Facebook that “the Cairo Comix Festival is opposed to censorship in all forms.”

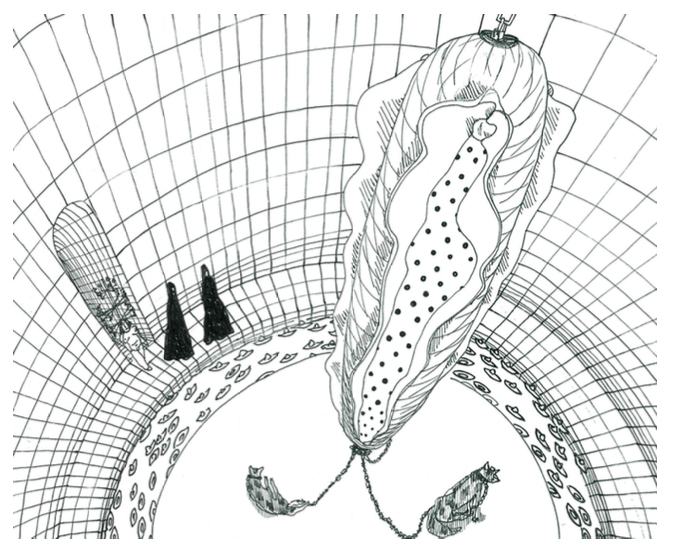

Maurice is in the midst of creating a symbolist graphic novel entitled Alcos. Though its story is opaquely mythic, it reads as a howl against fundamentalist religious conservatism, filled with slender clerics in tall hats and billowing black robes, looming menacingly around the subjugated body of the woman at the center of the tale.

“I was nearly expelled from my university for making this story,” says Maurice. “The administration told me that it was scandalous and immoral. My professor [at German University in Cairo] was fired for helping me with it. My hope is to find a publisher who will present the work without violent censorship.”

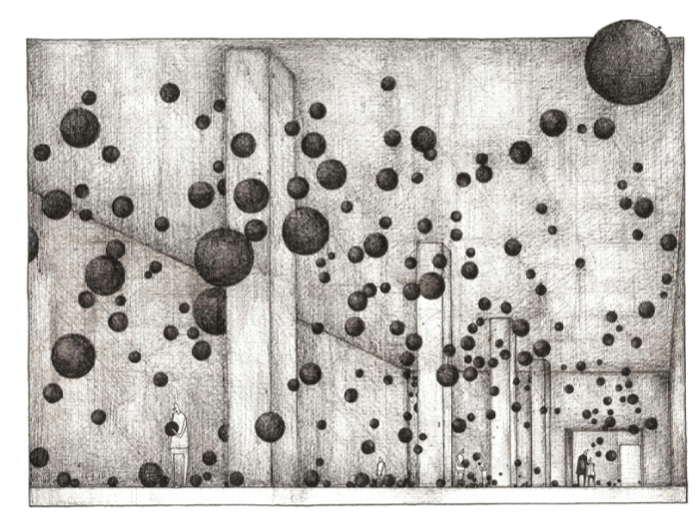

Many of the comics showcased at the festival address the emotional whipsaw of Egypt’s brief political opening. Mostafa Youssef's 2015 graphic novel Ialu is a dystopian fable about a city in which the government literally harvests its citizens’ dreams. The dreams are depicted in Youssef's densely hatched ligne claire hybrid style as iridescent black spheres that emerge from their dreamers' ears in moments of anxiety or despair. The story follows a “dream archivist” who comes to question his role in society. He begins to write his dreams on little paper airplanes, which he launches from high windows like a castaway stuffing messages in bottles. Ialu is a dark and oppressive tale, backlit with a persistent flicker of hope.

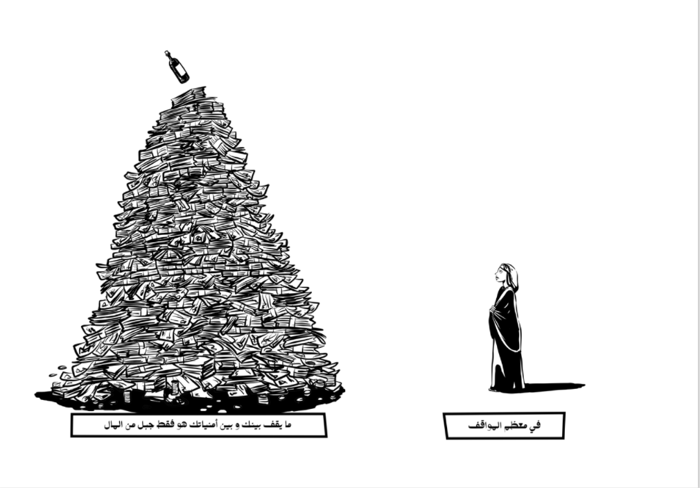

Like Ialu, Deena Mohamed’s magical-realist social satire Shubeik Lubeik literalizes the ragged and co-opted hopes of a people. The story imagines canned and bottled wishes, hawked on street corners as consumer goods to be bought and sold and—crucially—regulated by the government. Drawn with a simple, flowering ink line, the allegory follows a widow who scrapes and saves for years to buy a wish to honor the memory of her husband, only to descend into a Kafka-esque nightmare of bureaucracy and abuse of power.

In the mythology of Shubeik Lubeik, wishes, once acquired, can only be transferred consensually. The government uses every tool at its disposal—from red tape to imprisonment, starvation and torture—to convince the widow to hand over the wish. Her refusal to surrender in the face of an implacable and inviolable system reads as both inspiring in its courage, and heart-breaking in its futility.

In both Youssef and Mohamed's stories, a scrim of fantasy softens the depiction of a citizenry robbed of its agency, and a rueful celebration of individuals brave or foolish enough to stand up anyway. Their message of dissent is cloaked in just enough metaphor to keep the authors out of trouble.

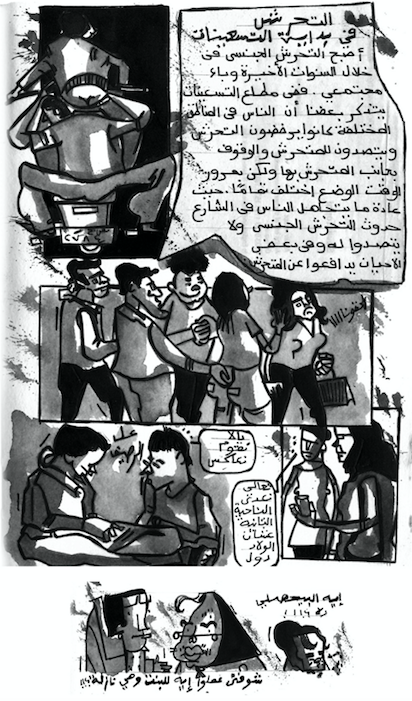

Other cartoonists at the festival approached their subjects with bare fists, particularly when it comes to gender politics in Egypt. In Traveler's Diary, Mai Koraiem uses a rough, expressive inkwash technique to detail the history of women's rights in Egypt and the Middle East. Through a journalistic narrative, Koraiem tells the story of the ascendance of a violent misogynist culture, and the unraveling of liberal feminist values she argues first found purchase in Cairo in the 1960s. In a small ongoing thread at the bottom of the page, Koraiem links the personal and political by including a comic strip narrating her own experiences with street harassment and sexual assault.

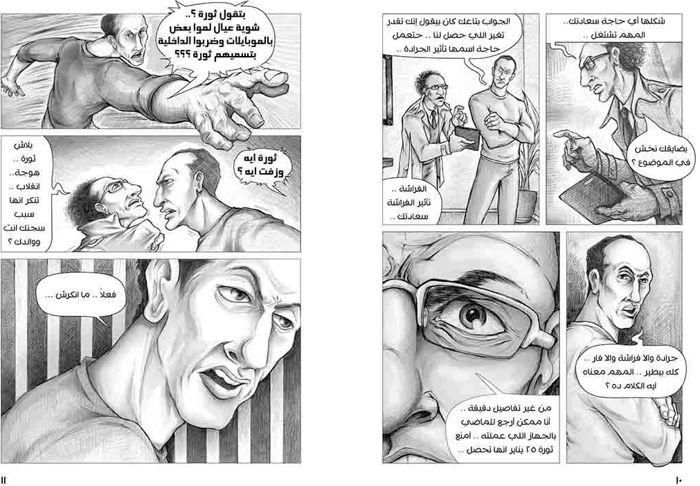

Hanan Hosney Alkarargy is the artist behind The Locust Effect, a science fiction story that turns an ironic, despairing gaze at the revolution and its fallout. It follows a time traveler's attempts to unravel the Mubarak regime through careful modifications of the historical timeline. Each alteration results in a monkey's paw-like backfire of unforeseen consequences. Alkarargy does not mince words when describing the central theme of the book: “The message is that fate is fate,” she says. “And that there is no hope.”

In Cairo, the worlds of street art and alternative comics are intimately linked. Alkarargy first met Magdy El Shafee in 2011, through an organized effort to vandalize the wall of the state police building in Nasr City. The expression was protected only by metaphor. “I remember Magdy, when confronted by a soldier, explaining that the art wasn't anti-government—it was simply a beautiful drawing of a ferocious dog.”

That kind of street art is no longer possible. “But people are talking, still,” says El Shaffei. “Every day people are waking up.”

The Cairo Comix Festival is, in its small way, an attempt to sustain that awakening.

“Okay. So we do not do graffiti anymore,” El Shaffei says, with a weary smile.

“But we still do comics.”

* Note: O’Neill’s travel to the Cairo Comix Festival was funded by the U.S. Embassy in Egypt as a cultural exchange. The embassy had no editorial role in this article.

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Egypt's Cartoonists Are Drawing a Lost Revolution"

Post a Comment